The Most Important Industrial Policy You’ve Never Heard Of

China's game-plan to beat the U.S in critical technologies.

If you’re a country that believes in sustaining an enduring peace, mutual cooperation, and playing nice with your neighbors, what do you do?

Naturally, you spend ~$100 billion to make worse versions of products your trade partners already produce and sell to you.

Xi Jinping may not have ever read Emerson, but definitely believes in self-reliance. With little attention from the policy or foreign affairs world, China rolled out the “Little Giants” program — one part of an incredibly expensive master plan called “Made in China 2025”. The ‘little giants’ program is one part of the plan that aims to re-shore critical technology manufacturing and eliminate points of foreign reliance for their associated components or services.

What Is a Little Giant?

Beijing has designated over 9,000 companies as ‘little giants’, or favorite children, to help climb the rungs of competitive markets and build homegrown critical technologies. Much like a jester cannot choose when to entertain his king, companies in China don’t really have a choice to accept / decline the ‘little giant’ designation.

Though, the title does come with perks:

Subsidies and tax breaks

Regulatory streamlining

Preferential dealmaking

The last perk is the most important — the designation opens doors to China’s biggest companies—many of them state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and ‘single champion’ companies. These 'single champions' are industry leaders that typically are a top-three global leader in the niche they serve and they generate the bulk of their revenue from 1 product for that customer segment.

CCP officials play an active role in these larger companies and are fully embedded within them, providing guidance, attending board meetings, and influencing activities. The same officials help little giants sell into established value chains, brokering ‘arranged marriages’ between little giants and single champions. In that backroom dealing, little giants win economically and the CCP gets a security win by hedging against external disruptions.

How does the ‘little giant’ designation process work?

Ministry of Internet and Information Technology (MIIT) committees, run by local CCP municipal officials are charged with finding and supporting ‘little giant’ companies, among other responsibilities.

These local officials want to climb the rungs of the bureaucracy and can do so by impressing their higher county / regional supervisory committee. Particularly, their interest is in maximizing power and status through a better posting rather than being tasked away in rural or impoverished regions of China.

You don’t get promoted by supporting a packaging company (even if that’s what the semiconductor value chain is missing), so officials are incentivized to swing for the fences so they look brilliant in the event that the companies work (hint: most do not).

Why does this matter to the U.S?

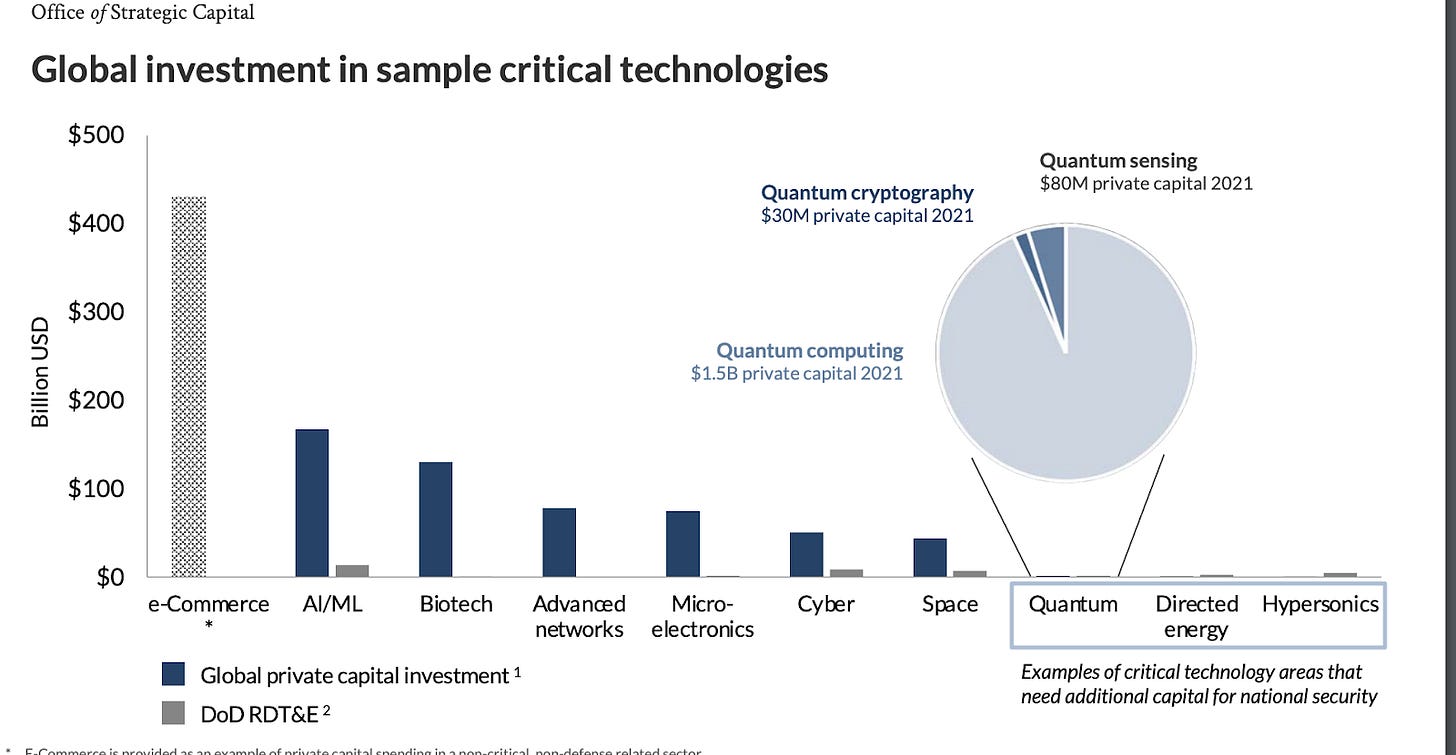

The U.S is getting outspent and outplanned on critical technologies by China, our near-power adversary, by 2-3 orders of magnitude. Spending doesn’t necessarily causally drive national security but it is definitely correlated.

Hope is not a strategy for security. If the U.S wants to retain its leadership for the next 50 years, it needs to take action to proactively ensure its current role as a security pole by planning around critical technology needs for our domestic supply chain security.

For contrast, it’s useful to look at an example of one public-private coordinated ‘partnership’ in China.

A Case Study in Public-Private Partnerships

At its core, the little giants program exists to eliminate the need for foreign purchases for any critical technologies in domestic products.

To reiterate, this is coordinated through arranged marriages. SOEs or SOE-owned companies are ‘encouraged’ to work with domestic vendors for critical technology components by CCP officials involved in the company through SOE ownership.

Previously a third choice at best, Hwatsing Technology's chemical-mechanical planarization equipment has already been widely adopted by Chinese chipmakers like SMIC, Hua Hong Semiconductor Group and YMTC.

All of the chipmakers listed are partially or entirely SOE-owned.

In another example, Xinjiang Goldwind Technology, a ‘single champion’ manufacturer of wind-turbines (with 20% of its ownership coming from SOEs), partnered with CRRC Hami Electric Co., a little giant (subsidiary of another SOE) that specializes in direct-drive permanent magnet wind turbines and power converters. With SOE involvement on both the seller and buyer-side, there’s very little friction to getting a deal done.

Wu Gang, the chairman of Xinjiang Goldwind's board of directors, is also the head of the CCP org within the company and was a member of the Party's 20th National Congress—a seat strategically filled from a pool of > 96 million Party members.

The U.S. Needs to Pay Attention

China isn’t just backing these Little Giants to ‘support entrepreneurship’ or bring back domestic talent in the Chinese brain-drain epidemic. Rather, this is part of a much bigger, long-term strategy to make China self-sufficient in critical industries—like semiconductors, AI, quantum computing, clean energy, aerospace applications among many others.

The U.S. depends heavily on foreign supply chains for these technologies—semiconductors, rare earth minerals, advanced battery components, and more. A huge chunk of the world’s chips come from Taiwan, which isn’t where you want them to be if you like having regular, predictable access to semiconductors.

If a point of escalation occurs, the U.S. could suddenly find itself cut off from these crucial supplies with China having homegrown alternatives to the critical technologies that the U.S has lost access to. The U.S, unlike China, has not built redundancies in place at the same scale to protect its future.

What’s the U.S. Doing About It?

The Department of Defense has some programs in place to help funnel capital to critical technologies; however, these are categorically insufficient.

The Office of Strategic Capital (OSC) is the U.S.’s analogy to China’s industrial funding giants like the “Big Fund” (~$100B critical-tech sovereign fund in China). The OSC’s main objective is to help the market de-risk investments in critical tech sectors—like semiconductors, clean energy, and biotech—by pairing public funds with private capital via debt facilities and small business investments.

The OSC has two primary lines of activity: SBICs (Small Business Investment Companies) and debt facilities. SBICs are investment managers, licensed by the Small Business Administration, who are given Uncle Sam’s money to deploy into critical technologies. This has some multiplier effect on the deployment of capital towards specific critical technologies.

The OSC aims to provide $10 - $150 million per project in loans to support domestic manufacturing, but they only have ~$1 billion to deploy over the upcoming year -- a drop in the bucket (3%) on a deal-market size of ~$30 billion across only AI and defense-related venture deals.

Another piece of the puzzle is the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), which focuses on bringing startup innovation into the defense sector. Since 2016, the DIU has awarded 450 prototype contracts valued at $1.7 billion, attracting $68 billion in private investments in turn.

The OSC, to its credit, knows that what it is doing isn't enough:

Scaling Up U.S. Efforts

If the U.S. wants to keep pace, we need to consider not only expanding programs like the DIU and OSC, but taking a more involved approach. Government-sponsored financial incentives are essential to reduce the risks for private companies, encouraging more significant joint ventures and partnerships that support critical technology sectors.

The OSC and DIU are showing promise, but their budgets are still small compared to the Chinese approach. Deploying ~$1 billion / year into critical technology is not going to fundamentally shift the U.S.’s position in the technology race. We need to create an environment where knowledge-transfer is encouraged and players are financially rewarded for the security value they produce for the U.S government.

The U.S. Needs to Build Ecosystems

China may stumble in execution, but one takeaway from the Little Giant paradigm is the power of ecosystems. Little giants don’t just pop up and survive on their own; they’re tied into a whole network of government resources, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and research institutes. If you’re a little giant, you’re not cold-calling potential customers—you're being nudged into deals with big state-backed players.

The U.S. could take notes on what’s working from these public-private partnerships. For example, picture Northwood Space — a small startup focusing on scalable satellite communication infrastructure. With support from a major player like SpaceX, and incentives from the USG, Northwood could more easily overcome some of its big potential challenges—like connecting different types of satellites into one cohesive communication network and ensuring 24/7 reliability. The established aerospace giants could provide the expertise and infrastructure to deal with interoperability issues and large-scale deployment.

Similarly, Sila Nanotechnologies, which works on advanced silicon-based battery materials, faces huge hurdles in scaling up production and integrating into existing manufacturing processes. Partnering with major automotive companies like Tesla or Rivian, with a little nudge from the government, could give Sila access to production lines, supply chains, and the experience needed to move from prototype to mass production.

Most people have long erroneously believed that Pax Americana is a manifest destiny of sorts. The truth is that America’s pole position in the global order is far from predetermined and in reality — is in danger.

The future we want our children to inherit is sitting on the other side of a coordinated plan to drive private innovation towards public security. We can enshrine our future, but we can’t sit around hoping that someone else does it for us.